Sweden's Sami fear for future amid rare earth mining plans

Sweden's indigenous Sami fear they will lose their livelihood and culture if plans go ahead to mine a large rare earths deposit located on their traditional reindeer grazing grounds in the far north.

Rare earth elements are essential for the green transition, including electric vehicle battery production, and the large discovery made in Sweden in early 2023, as well as an even bigger one in Norway in 2024, has boosted Europe's hopes of cutting its dependence on China.

The Asian country is home to 92 percent of the world's refined rare earth production and 60 percent of rare earth mining.

Almost a kilometre underground in the Arctic town of Kiruna, Sweden's state-owned mining company LKAB is blasting an exploration tunnel from its iron ore mine to the neighbouring Per Geijer deposit, to assess its potential.

Its machines are advancing by five metres a day.

"We don't have any rare earths exploration or mining in Europe, so this has great potential," LKAB vice president Niklas Johansson told AFP on a recent visit.

However, there are "also a lot of challenges", he added.

- 'Legal hurdles' -

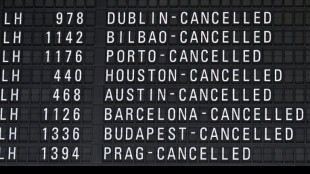

"There is political will" to mine the deposit, but also "a lot of legal hurdles, permitting processes, which the new rules are supposed to make easier," he said.

"But we still haven't seen any of it."

The "new rules" he's referring to are 47 "strategic projects" regarding rare earths and strategic materials drawn up by the European Commission in March 2025 and fast-tracked for approval.

Per Geijer is one of them. In theory, the mining permit procedure is supposed to take a maximum of 27 months.

LKAB has yet to receive its permit, and Johansson is seasoned enough to know it could take much longer.

"We might be looking at 10 years just to get the permit", and then "a couple of years in order to make a mine".

- 'Existential threat' -

The prospect of a mining eldorado in the region has Sami reindeer herders worried.

"We are really quite desperate," said Lars-Marcus Kuhmunen, a herder and head of the Gabna Sami community.

"We could be the last generation of Sami in this area," he said. Kiruna, he added, "will be a black spot on the map".

Their entire livelihood is at stake.

The planned mine "is set to obstruct the only remaining seasonal migration route connecting the winter pastures and summer pastures", explained Rasmus Klocker Larsen, a researcher at the Stockholm Environment Institute.

"The risk is that people are pushed to quit herding, and Sami customs and knowledge are not handed down to new generations," he added.

Larsen is currently conducting a study on the impact that mining projects on Sami lands have on the indigenous community's human rights.

Kuhmunen said the rare earths mine would cut the community's land "in half".

"Then we can't conduct our traditional reindeer herding as we have done for 400-500 years."

LKAB insisted the company would find a solution with the Sami.

"The Per Geijer project is still at an early stage with a lot of studies ongoing, including on which protection, adaptation and compensation measures will need to be taken regarding reindeer herding," LKAB sustainability director Pia Lindstrom told AFP.

"We think it is possible for both of our businesses to continue to operate and grow," she said.

- 'Culture, not money' -

But the Sami and LKAB representatives "don't speak the same language", argued Kuhmunen.

The discussions always revolve around financial compensation, he said.

"We don't want money," he stressed.

"We want our culture and reindeer herding to improve."

According to LKAB, the rare earths in the Per Geijer deposit are located in what is mainly an iron ore deposit, and can therefore be produced as by-products.

LKAB intends therefore to continue to extract iron ore at the Kiruna mine as it has since 1890, in order to make the rare earth and phosphorous mining profitable.

While the Per Geijer deposit is the second-biggest known deposit in Europe, it remains small on a global scale, representing less than one percent of the 120 million tonnes estimated worldwide by the US Geological Survey.

M.Wallin--StDgbl