UK's crumbling canals threatened with collapse

On a misty winter's day in the English midlands, engineers struggled to drag stranded narrowboats from a waterless, mud-filled canal that collapsed weeks earlier, in a delicate, multi-million-pound rescue operation.

The sight starkly illustrated an ongoing battle to maintain the UK's historic, yet deteriorating, waterways.

Britain's canal network "is facing pressure it has never faced before," said Charlie Norman, director of campaigns at the Inland Waterways Association (IWA), an independent charity advocating for the upkeep of the UK's canals and rivers.

"The entire canal network is vulnerable," Norman added, pointing to the "increased effects of climate change" such as drought in the summer and heavy rain in the winter.

"Inadequate funding across the sector" has provoked an "overall deterioration" in the 4,700 mile-long (7,600 kilometre) network, they said.

Britain's 200-year-old canal network was once the backbone of the country's economic transformation during the Industrial Revolution, but is now crumbling, experts say.

About a dozen workers were overseeing the complex operation to rescue three narrowboats stranded in a canal in Whitchurch, on the English-Welsh border, last month.

Watching from an empty canal bank and wearing a high-viz jacket and white hard hat, was Julie Sharman, the chief operating officer of the Canal & River Trust –- a charitable organisation in charge of maintaining some 2,000 miles (3,200km) of waterways across England and Wales.

Behind her were two 20-tonne narrowboats waiting to be rescued by an imposing winch machine in a nearby field with the help of a specialist excavator.

- 'Tough decisions' -

"There's no disguising the fact that we do need more money to look after our canal network," she told AFP.

"People sometimes think canals are looked after by local authorities or by the government, and they're not. They're looked after by us, as a charity," she said.

The trust is investigating the Whitchurch breach, but Sharman said "our engineers have to make tough decisions every week" about which projects to tackle and "there's always a very long list of things we would want to do".

"Small breaches and failures have happened since the canals were built," she added, but "it's rare to have a breach of this scale".

In January 2025, there was an earlier canal collapse in Bridgewater, northwest England, which led to just under two miles of the canal being drained of water.

The Canal & River Trust, the largest authority, says its fixed annual grant of £52.6 million ($71.8 million) from the government, amounts to just 22 percent of its annual income, but that will reduce by five percent from 2027 for the next decade.

The rest, some 78 percent, is funded by the charity's own investment and self-generated income, including user fees and fundraising, supported by thousands of volunteers.

Last week, the UK government pledged an additional £6.5 million funding for the trust "to help build long-term resilience across the network".

"Our historic canals and waterways are not only world famous and precious to communities across the country -- they are also a vital part of our national infrastructure," said Water Minister Emma Hardy.

British Waterways, a statutory body of the UK government, ceased to exist in 2012 and handed maintenance of canals and rivers to a series of 144 navigation authorities.

It was believed the move would diversify funding potential allowing bodies to tap into government grants, commercial revenue and charitable donations.

- Transport, leisure, homes -

"Before canals, transporting goods across Britain was limited to horse and cart," said historian Mike Clarke.

The advent of the canal greatly increased the nation's capacity to transport goods.

After declining in use, "a restoration movement came about in the '60s" and people began to live on canal houseboats, Clarke said.

Now more than 35,000 boats are registered with the Canal & River Trust, plying the network to transport goods or just for pleasure. And about 15,000 people are said to live on canal boats moored on the banks.

Matt Gibson, 52, moors his sage-green houseboat, bedecked with plants, on the Regent's Canal near central London.

He moved in during the pandemic "to explore a different way of living".

"I get a bit spooked when I can hear drunk people outside at night," he told AFP. "I do love living here, though -- I don't need much more space to live".

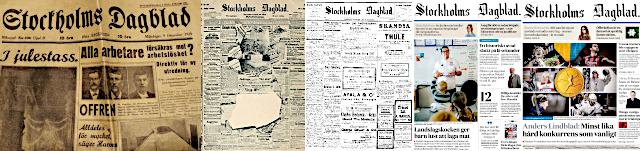

M.Wallin--StDgbl